Monheim Triennale II 2025

Monheim Triennale II

July 2 – 6, 2025

Monheim am Rhein, Germany

Review by Ken Waxman

Photos by Susan O’Connor

Perfecting the exclusive ideas which characterize the Monheim Triennale, this year’s edition in early July demonstrated how numerous international experimental artists could convene to showcase significant projects and ad hoc improvised sessions.

A city of slightly more than 43,000 people, 22 kilometers from Köln and 26 from Düsseldorf, Monheim am Rhein as its name suggests, is defined by its proximity to the Rhine river with almost all The Triennale’s venues located either on a refurbished ship docked on the river, or within walking distance of the fast-flowing water.

The festival name needs explanation, though. Designed as a three-year cycle, the first year called The Sound, creates sound art installations throughout the city. The second, called The Prequel, creates artist residences that allow selected musicians to brainstorm original projects while interacting with other invitees. Finally, The Triennale itself is a festival of concerts that showcase these realized projects as well as improvised and ad hoc sessions. That is why 2025’s edition was called Monheim Triennale II, since it was the second edition of the Triennale realization. Use of lowercase letters for some of the artists’ names and titles of their works, were part of the festival’s program.

With the number and variety of talents invited, it was sometimes difficult to discern an overriding program definition, which was perhaps the intention. Variants of progressive political viewpoints were verbalized by some performers, but not to the point of annoyance. In most cases the music spoke for itself.

A prime instance of this was New York-based trombonist/vibraphonist Selendis Sebastian Alexander Johnson’s signature project, Reflections on the German Revolution (1918~1919, and more), which ended the evening’s performances at the Festival Boat’s main stage on July 3.

Featuring alto saxophonist Francesca Fantini; tenor saxophonist/clarinetist José Fernando Solares; trombonist Moritz Wesp; pianist Hans Young-Binter; guitarist Christoph Götzen; bassist Caroline Morton and drummer Josh Mathews, the octet roared through Johnson’s suite as the composer moved from plunger trombone moans to anvil-like vibraphone key hammering while leading the group through the sinuous composition.

Without lyrics, the band referenced the ferment engendered by the Socialist strike against German conservatives and the monarchy with alternately lamenting and wailing timbres.

Often the drummer broke up his cowbell and cymbal accents with thickened martial-like ruffs, sometimes doubled with tough double bass string slaps and arco rub.

Additionally, military bugle-like blasts from the brass underlined the population’s militancy. Simultaneously and as importantly, reed multiphonics, scooped wheezes and slippery flattement, double-tongued plunger trombone smears, shaking guitar-string flanges, and keyboard clips and plinks confirmed the turbulent syndicalism of the population at that time. Without overemphasizing the programmatic echoes, the composition advanced on its own, with theme recapitulations, orchestral riffs and expansive soloing intertwined as the narrative worked its way to a speedy, droning finale.

A much more obvious concept of program music took place the next night in the boat’s concert hall with the signature project by German composer Heiner Goebbels. Entitled The Mayfield, it is named for an old train station depot in Manchester, England where the piece was first rehearsed and staged.

In addtion to the composer’s piano preparations, the ensemble consisted of Gianni Gebbia playing soprano and baritone saxophones; Nicolas Perrin on guitar and electronics; percussionist Camille Emaille; Cecile Lartigeau playing ondes martinot, and Willi Bopp contributing sound design. Although locomotive-like sounds occasionally crept into the performance, with railway-like inferences usually emanating from programmed wave forms, the vitality of the creation depended as much on the players’ responses as the composition’s shape.

Beginning with replication of railway-crossing noises in the form of harsh bell-ringing, percussion wallops and stopped piano-key pressure, the piece soon took on a breezier interface with Gebbia alternating baritone smears and soprano sax tongue slaps, aviary squeaks and reed quacks, and with Perrin adding metallic flanges, angled rubs and metallic crunches. Emaille’s stroking of a violin bow on her drum tops, and smacking cymbals and an oversized triangle alongside Goebbels’ rattling of internal piano strings added to the precise cacophony. However, with unexpected noises at times reflected back into the instrumental mix from the sound design while electronics were overdubbed over individual timbres, it was Goebbels’ processional comping that kept the performance on an even keel.

Eventually, concentrated oscillated drone and string scrapes ended the piece which had formerly seesawed between projection and vibrations.

Echoes of the concepts reflected in these breakthrough compositions also affected Korean-American violinist/vocalist yuniya edi kwon’s signature project silver through the grass like nothing that was the final boat set on Saturday night.

A meditation on her experiences with illness, grief and personal and societal changes, the theatrical composition was further ingrained with contrasting and intersecting musical strands from notated and improvised music and Korean folk timbres. Assisting kwon were violinist Darian Donovan Thomas; violist Joanna Mattrey; cellist Tomeka Reid; bassist Henry Fraser, and both Dudù Kouate and Nava Dunkelman playing a variety of percussion and ritual instruments.

Contrasting echoes of various genres and cultures, the melodic transformation in silver through the grass … built up from sonic fragments where at points the strings’ astringent staccato lines gave way to sweetened unison harmonies that could have come from a so-called classical string quartet.

Still, those interludes had little time to settle before they were broken up by cymbal vibrations, balaphone-like reverberations and Africanized percussion thwacks, then squeezed back into hoedown-like echoes.

Meanwhile, kwon’s ululating tunes sung in a mixture of Korean, English and vocalese were defined by her varied persona, with angry basso cries taking their place alongside happy child-like trills, operatic lyricism and strident screams while various words and phrases were projected onto a screen at the rear of the stage.

When the string section built up to bellicose staccato stabs, and kwon’s vocal output turned to either pained or painful yowls, a descending double-bass thump signalled the finale, which took the form of a slowly diffusing group drone.

Australian guitarist Oren Ambarchi’s signature Hubris project was the first mainstage boat concert on July 3. Designed with a variation of dynamic broken chord rhythmic and melodic designation, the project explicitly eschewed vocals; that is except for brief phone interruptions by crys cole.

Essentially the piece revolved around how gradual changes in dynamics and tempos could be sensed, even as five guitarists – Jules Reidy, Phillip Sollmann, Fredrik Rasten, Marcus Pal and Ambarchi – projected an assembly line of nearly identical repetitive licks and strums. Momentum was preserved throughout, even during those interludes when some of the guitarists dropped out. The tremolo variations were further intensified by oscillations from Konrad Sprenger’s computer programming, and given an equally thick and uncompromising accompaniment from Johan Berthling’s electric bass pulse and a percussion axis from dual drummers Will Guthrie and Andreas Werliin.

Mats Gustafsson’s winnowing flute licks offered a brief respite from the sublunary massed string propulsion early on, but midpoint unison overblowing from his baritone saxophone and Sam Dunscombe’s bass clarinet added more pressurized timbres – albeit of a darker hue – to the ongoing concentrated sound.

Then, just as it seemed as if all sounds had melted into a nearly opaque mass, a more rock-like, almost danceable rhythm from the whole band was heard. Reed noodling with Free Jazz-styled dissonance helped direct the narrative patterning towards more accessible polyphony by the finale.

A number of sets were directed towards voice and singing, but only American trumpeter Peter Evans’ signature creation, Being & Becoming + Voices presented on two succeeding nights utilized a larger ensemble.

In addition to Evans on trumpets, the band included Joel Ross playing vibraphone, Nick Jozwiak playing bass and synthesiser, and drummer Tyshawn Sorey. The vocalists were Sofia Jernberg, violinist/vocalist Mazz Swift and Alice Teyssier, who also played flute.

Before the standing-room only crowd at Sojus 7, Evans directed between strained pocket trumpet buzzes and regular trumpet obbligatos while Ross’s pops belabored the vibes’ bars, and a processed electronic drone underlined the proceedings.

Among the performance variations, which ranged from near-atonal to Bop Swing, vocal contrasts became more obvious. Jernberg stuck to studied bel canto reading, Swift was more rhythmic with vocal echoes, and Teyssier the most free with her aggressive flute forays often serving as entrees or additions to her all-out vocalese.

One project that was completely vocal-oriented took place Saturday afternoon in the mid-19th Century Altstadtkirche next to a small park with an arresting sculpture incorporating stylized human figures criss-crossed with sculpted barbed wire, and whose Magen David honored those murdered in the Holocaust.

Samesoul Maker created by American Darius Jones, whose advanced alto saxophone work was showcased in duo and solo form elsewhere during the festival, was through-composed. With four singers – Gelsey Bell, Aviva Jaye, Sunder Ganglani and Paul Pinto – vocalizing the composer’s invented language while sounding handheld bells – the performance was accompanied by the prepared, pointed and tapered tones from vibes and a circular shell played by Levy Lorenzo, that adumbrated and accentuated the ongoing vocal dialogue in Jones’s signature project.

Enhanced by shaking those tiny bells, and with hand gestures, the singers expressed the libretto in contrapuntal and concordant; fragile and ferocious solos and duos, often layering the timbres to widen or foreshortened phrases. Singular expressions using the four’s bass, baritone, alto and soprano tessiture projected and personified the verbal abstractions.

In contrast, You Are the Other Lung in my Chest, the signature project of Pakistani-American Shahzad Ismaily, accentuated its message with verbalizations in Farsi, Arabic and English.

Ready to snatch from James Brown the title of the Hardest-working Man in Show Business, Ismaily was featured in no fewer than seven Triennale sets. In this set, whoich took place on the mainstage Friday evening, playing electric bass, synthesizer, drum kit or percussion, he was accompanied by Miriam Elhajli, playing both guitar and piano, and guitarist Yousif Yaseen while poet Ghayath Almadhoun and poet/translator Haleh Gafori commented on the Middle East situation with an emphasis on Gaza.

Luckily Almadhoun’s gift for sophisticated metaphoric language, and Gafori’s knack for bringing out the universal themes of love, tolerance and understanding from the works of 13th century mystic poet Rumi, made the set a showcase for poised instrumental quality and versification rather than an exercise in pointless polemics.

Overall these vocal-affiliated projects complemented the majority of Triennale II’s sets that were primarily instrumental, with musicians taking advantage of the freedom and idea-generation experienced during The Prequel to put into practice notable improvisations and definitions. The starkest demonstration of this concept took place during a series of noon-hour concerts in the 15th century Marienkapelle, situated almost directly across the road from the Festival boat.

The standouts involved solo reed displays by Swede Mats Gustafsson, American Darius Jones, and Italian Gianni Gebbia; string recitals by Americans Joanna Mattrey and Darren Donovan Thomas; and a duo of Canadian vocalist Julia Úlehla and Scot Brìghde Chaimbeul playing a small pipe.

Outstanding trio sets, both of which took place in the Festival Boat’s bow, were that of Ghosted with guitarist Oren Ambarchi, bassist Johan Berthling, and Andreas Werliin drums, as well as Merope which showcased the guitar and electronics of Bert Cools, Indre Jurgelevičiūté playing kanklės, a Lithuanian plucked chordophone, and Shazad Ismaily on synthesizer and drums.

Should there be any doubt as to how varied a solo saxophone rendering could be, it was shattered in the small Marienkapelle. Friday’s alto saxophone set by Jones used the spatial architecture of the structure to reverberate with refractions of reed-overblowing and multiphonics. Along with squeaking split tones and brittle squawks, there were hints of Blues and gospel roots. With his hushed in-and-out breaths and marked pauses, these strained echoes made more sense when Jones explained that the piece was a variation of a tune sung by Parchman Farm inmate Henry Jimpson Wallace in 1948 and recorded for no compensation by folklorist Alan Lomax.

Going back further in history, Gebbia paced soprano saxophone improvisations with pre-recorded, ancient music percussion and string samples from his cellphone during his set on Saturday. Circling the small stage as he played, he pivoted back and forth between dissonance encompassing ear-splitting squalls and note flutters with obviously melodic fare that touched on lyricism and Jazz standards. Harmonizing with the samples, he slipped from louder and higher reed smears to a touch of song-like melody at the end.

The only solo reedist to play two different instruments, Gustafsson’s set at noon Thursday at this late Gothic pilgrimage chapel, used a similar approach to both instruments to overcome their timbral differences. He emphasized shrieks, flutters and yelps to subvert the flute’s graceful reputation, wrapping up that interlude by simultaneously grunting and trilling through the transverse instrument. Atonal ferociousness characterized his baritone saxophone soloing. Tongue-slapping wails, heavily breathed basso gusts and altissimo screeches cemented this impression. Gustafsson bolstered the split tones and buzzes with key percussion, and wrapped up the set with shakes and peeps from a suddenly produced mini mouth organ.

Mattrey’s Saturday afternoon set was an exhibition of prestissimo playing as she accentuated both spiccato and sul ponticello bowing, and with interludes where she suddenly output a series of twanging banjo-like pizzicato plucks. Moving to wider variations, she slid downwards in pitch to create jagged variations, then worried the same note over and over at the conclusion.

Field recordings also figured into Thursday’s early afternoon solo set by Donovan Thomas as he played bird calls alongside the violin thrusts. and verbalized snatches of poetry and songs with a nautical theme. As his voice rose and fell, so did the fiddle glissandi.

Since the vocalized phrases intertwined with arco melancholy and harder guitar-like plucks, an individual but somewhat blurred idea of his identity was realized, yet questioned again as the field recordings stopped and tinkling sounds from a miniature music box took centre stage.

With a distinctive drone introduced as Chaimbeul squeezed the pipe’s bellows under her arm with sounds emanating through tone holes on a chanter, Úlehla abandoned words and instead began a keening dirge that sped up as Chaimbeul’s pipe timbres grew faster and faster throughout their duo set at Marienkapelle.

Standing up from an initial lotus position, even without lyrics, Úlehla suggested folkloric roots with sea shanty-like rhythms. When the piper intensified the reel she was huffing with a tremolo chanter buzz and rhythmic foot tapping. Úlehla continued her singing as she walked through the audience, up into the balcony and completed her vocalized yearning responses on the stage beside Chaimbeul.

Of the notable trio sets in the boat’s smaller bow space, one emphasized the adaptability of ethnic instruments to modern improv, while the other was resolutely post-modern.

Using the sonic resources emanating from the multi-string kanklės or Baltic zither played by Lithuanian Indré Jurgelevičiūté Thursday afternoon, a simple ballad-like form was established, unencumbered by the flanges created by some of Belgian guitarist Bert Cools’ numerous plug-ins and foot pedals, and the whooshes from Shazad Ismaily’s synthesizer.

Overall, mechanized oscillations vied with simple guitar strums and chordophone expressions, which varied from every which way flailing to more focused rhythmic flutters. Jurgelevičiūté’s few vocalized asides were usually drowned out by the instrumental thrust, but the traditional-modern interface came across clearly.

Dealing in the sort of slowly unfolding musical transformation perfected by bands like The Necks, the Ambarchi/Berthling/Werliin trio set on Friday depended on Berthling’s powerful but only slightly varying pizzicato plucks for its rhythmic underpinning. As his broken chord pattern additions gradually altered textures and dynamics, the piece’s shape was transformed, but in such a languid fashion that at points, it was almost as invisible as it was indivisible.

Meanwhile Werliin’s use of conga drum pumps as well as pressure from regular kit added to this seemingly unstoppable beat as did Ambarchi’s occasional string flanges and stops. Modulated shakes and pops from the open-tuned guitar or synthesizer dial-twisting didn’t alter the hypnotic foot-tapping rhythm, so that even a sudden group stop made it seem as if this were a pause in a still-continuing narrative rather than a definite conclusion.

These slow sonic transformations were an important part of some of many sets designed for the Triennale. Two that stand out were piper Chaimbeul’s multi-media presentation which took place on the boat’s main stage Friday evening, and a much less visual but more visceral interpretation of Patti Smith’s music by four bassists and a drummer at Sojus 7 Thursday evening.

Entitled where the veil is thin, Chaimbeul’s signature project linked her small pipes and those of bagpiper Jamie Murphy, featured rear-screen projection of Isle of Skye country scenes by John Smith and Jonny Ashworth, and included the foreground participation of dancer/performance artist Molly Scott Danter.

Loosely based on Gaelic folk tales about a wild old lady who creates winter conditions, the piece began with Danter squirming under a tarp placed just below the stage. As the pipers’ tremolo drones mixed with a pre-recorded voice recounting the fable’s details in Gaelic, Danter exposed one limb at a time until she rolled onto the stage itself for a series of gyrations where she kicked her legs in the air one at a time; turned somersaults, rolled on the stage floor, and stretched herself into various contortions as the dual pipes peeped with calliope-like airiness or lowed percussively.

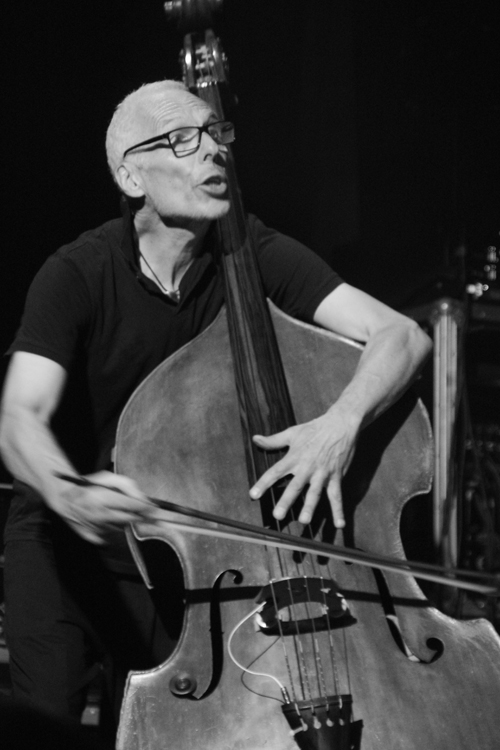

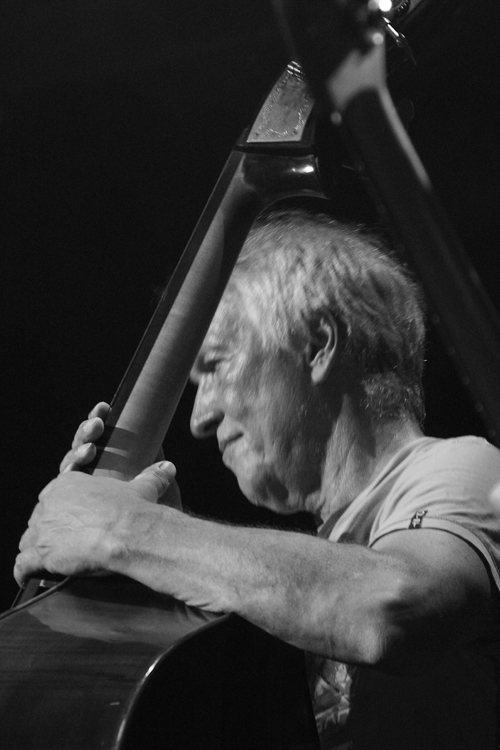

Unadorned except for interjections of field-recorded male and female voices, Thursday’s Break On Through Patti Smith tribute instead concentrated on the virtuosity that could be expressed balancing the power pumps from all German — electric bassists Adrian Breuer and Henri Halbach — and the acoustic basses of Jan Peter Welsch and Achim Tang, the latter of whom played in almost as many Triennale ensembles during the four-day festival as Shazad Ismaily.

Breuer’s consistent straight-ahead patterning made his part as much a salute to the beat of legendary Motown bassist James Jamerson as Smith’s compositions, while Blues inflections, popping whacks on the instruments’ woody backside and other string modulations defined the acoustic input. Tang was even able to play an entire sul ponticello bow solo without interrupting the music’s powerful flow.

Monheim Triennale II offered about 50 different presentations during its four-day run, with more than could be squeezed into this report. Its second iteration clearly established its position on the international creative music scene. Thus anticipation of what the next Triennale series will germinate remains high.

Be sure to visit the continuously updated individual Artists‘ pages on Jazzword.com for CD reviews

by Ken Waxman and more performance portraits by Susan O’Connor.

All material on Jazzword.com is copyrighted by the creators. For reproductions of photos or articles, please email [email protected]